To Build a Backfire

Inspired by Jack London’s “To Build a Fire.”

DAY HAD DAWNED COLD AND GRAY WHEN the woman turned aside from the main fireline. She climbed the high earth-bank where a little-traveled game trail led east through the pine forest. It was a high bank, and she paused to breathe at the top. She excused the act to herself by looking at her watch. It was nine o’clock in the morning. There was no sun or promise of sun, although there may not be a cloud in the sky. It was a smoke inversion day. However, there seemed to be an indescribable darkness over the face of things. That was because the smoke made the sun absent from the sky. This fact did not worry the woman. She was not alarmed by the lack of sun. It had been days since she had seen the sun.

But all this—the distinct fireline, no sun in the sky, the great smoke, and the strangeness of it all—had no effect on the woman. It was not because she was long familiar with it. She was a newcomer in this land, and this was another megafire. The trouble with her was that she was not able to imagine. She was quick and ready in the things of life, but only in the things, and not in their meanings. A smoke inversion and falling temperatures meant rising humidity. Such facts told her that it would be difficult to start a backfire, and that was all. It did not lead her to consider her weaknesses as a creature affected by smoke. Nor did she think about firefighters’ general weakness, able to imagine only within narrow limits of heat, wind, and fuel moisture. That it should be more important than that was a thought that never entered her head. From there, it did not lead her to question incoherent commands or to thoughts of heaven and the meaning of a woman’s life.

She had taken the long game trail away from the fireline to scout the possibility of starting a backfire when the inversion lifted. She had been dispatched with a squad but they had stopped at a small smoldering spotfire. They stayed there a long time and debated whether backfires would burn and what would happen when the inversion lifted. She went ahead, following her boss’ orders to find out where to build a backfire. She would be in spike camp by six o’clock that evening. It would be a little after shift, but her fire crew would be there, a camp fire would be burning, and a hot supper would be ready. As she thought of lunch, she pressed her hand against the package in her firepack. It was wrapped in a bandana, and riding on top of her fusees. Otherwise, the bread would be smashed. She smiled contentedly to herself as she thought of those pieces of bread, each of which enclosed a generous portion of processed meat. She plunged among the big pine trees. The fire was not well established here. Several hours of dew had fallen since the last flame had lept. She was glad she was without a heavy pack. Actually, she carried a lot of safety equipment, a fire shelter, a first aid kit, a pulaski, fusees, and her lunch wrapped in the bandana. She was surprised, however, at the ample dew. It certainly was damp, she decided, as she rubbed her nose and face with her leather-gloved hand.

Watching at the woman’s heels was a big native wildfire. It was part natural fire and part burn-out operation. It had burned through clearcuts and plantations and overgrown landscapes made sickly by suppressing fire. Gray-ashed and not noticeably different from its sister, the wildland fire. The wildfire was worried by the great dew. It knew that this was no time for burning. Its own feeling was closer to the truth than the woman’s judgment. But the wildfire sensed the danger. Its fear made it question eagerly every movement of the woman as if expecting her to go into camp or to seek pumps and hoses somewhere and build a hose line. The wildfire had learned about hoses, and it did not want hoses. Otherwise, it would smolder itself into the duff and litter and find shelter from the cold dew. The woman went steadily ahead. She was not much of a thinker. At that moment she had nothing to think about except that she would eat lunch at the fire’s crest and that at six o’clock she would be in camp with her crew. There was nobody to talk to; and, had there been, speech would not have been possible because of the tobacco chew in her mouth. Once in a while the thought repeated itself that it was very damp and that she had never experienced an order to build a backfire in such humidity. Empty as the woman’s mind was of thoughts, she was most observant. She noticed the changes in the fuel load, the live fuel, the dead fuel, and the amount of ladder fuel. And always she noted where she placed her feet. Once, coming around some brush, she moved suddenly to the side, like a frightened horse. In the ground she saw what could be a yellowjackets’ nest. She never knew how her body would respond to yellowjacket stings. She carried Benadryl and an epinephrine needle. Usually the stings produced nothing but painful welts. Still, yellowjacket stings meant delay as she would have to slow down, monitor herself, and possibly treat the stings. She did not want delay as it might diminish her status among the crew.

The woman found an unburnt area heavy with dead fuel. She knew this would be great trouble later in the day after the inversion lifted. Then the fire would roar back to life. If it devoured this fuel, it could charge over their skimpy handline. She decided this was the place to set to work. She threw down her backpack and removed her fusees. She hoped the rest of her crew would catch up soon. Boredom should have overtaken their debate over backfires and inversions by now. And their smidgeon of work ethic should push them out of their comfortable laziness. But she felt she could not wait. She jammed a fusee on a stick and ignited it with an intent to burn narrow chevron strips that would safely burn out the flashy fuel while not enkindling heavy fuel. She planned to burn out the soggy flashy fuel before the inversion lifted and woke up the fire. The heavier fuel still glistened with dew. With no flashy fuel, this heavy fuel would not ignite even when it dried out. Then the ravenous wildfire could devour nothing and it would not travel through a blackline here.

Her plan was working well. Small flames annihilated the grass and loose litter while not even broaching a smolder from the hundred hour fuel. As she worked, she confidently thought that her smoke would summon the boys, her crew, to scamper over so they wouldn’t miss the fun. She didn’t call them because she didn’t like talking on the radio and it meant spitting out her chew. She liked to lead quietly by example. She would burn-out all of this area by herself and begin building the backfire. When the boys came they would be amazed and her stature would grow. Then it happened.

She stepped on a yellowjacket nest. They came swarming out before she had a chance to respond. They stung her on her face and wrist and hands where her shirt and gloves didn’t cover. She sprinted away as quickly as she could, swatting and cursing. She felt multiple stings, especially on her hands where they had crawled into her gloves, and on her shins at the top of her boots where they had crawled up her pants legs. This could be serious. She felt the swelling in her hands but no tightness yet in her breathing. She sat calmly for a while, monitoring her body’s reaction. Then she looked back at her backfire. It was dying. Only a few smoldering smokes left. When she staggered back to her backfire, she could see some of those smokes were her fusees spitting out the last of their magnesium and acrid smoke. They must have been flung out into her backfire and ignited when she ran away from the wasps.

Only one sputtering fusee was still usable. She reached for the fusee but her swelling hands had become numb and unresponsive. She could not grasp the fusee. She slapped her hands against her chest and thighs to bring back their senses. It only made her chest and thighs ache. She tried to grasp the fusee with her forearms, but its sparks were painful so she let it drop. It was nearly finished anyway.

She looked at her backfire and saw her burning-out of the flashy fuel was almost complete. But there was still an unburnt area that made their fireline vulnerable when the inversion lifted.She desperately wanted to complete her backfire, even though the yellow jackets sting’s increased her pain and numbness. She spit out her chew so she could call for help using her radio, but her hands couldn’t make the radio work. When she tried to kick the radio back to her pack so she wouldn’t lose it, she noticed she could no longer feel her feet. She took a few steps and felt as though she were flying because she couldn’t feel contact with the ground. She decided she needed to take benadryl. She clumsily used her forearms and numb hands as clubs to beat her first aid kit out of her pack. Because her lips had gone numb, she used her teeth to tear into the kit. She wedged the benadryl bottle between her forearms and tried to open the childproof cap with her teeth. She couldn’t do it. Her eyelids were swelling and her vision grew blurry. She thought of panicking but then she realized her breathing remained unimpaired. She breathed calmly and with strength. She could get through this, she decided. What goaded her most was not the pain and numbness and inability to make her hands and feet function. It was that she had not completed her mission to build a backfire. Most of all, she needed to build a backfire.

She remembered a trick Ol’ Buddy had told her about. You could take a dried evergreen bough, lay it over some coals until it ignited. Then you could drag it over your fuel to burn-out. It works as good as a drip torch, Ol’ Buddy claimed. Under her swollen eyelids, her vision suddenly sharpened. She got up and started to stagger toward some fallen conifer branches. She had to look down at her feet to make sure they contacted the ground because she couldn’t feel them.

She reckoned that she needed a small bonfire to secure a source of ignition, then she could use it to keep lighting many fir boughs on it and drag the flaming boughs to where they were needed. She used her clenched forearms to drag heavier fuel to where one of her fusees had caused a small smolder. It was under an old fir tree so sticks and branches were plentiful and the old conifer’s foliage was high enough that she didn’t worry about a crown fire. Soon the fuel pile burst into a small crackling flame. She laid on a fir bough and it ignited. She dragged the flaming branch across the moist flashy fuel. It worked a little. But the fuel was so damp that it would take a lot of flaming boughs to accomplish a burn-out similar to what her fusees had done. She piled more fuel on her bonfire and collected more dead boughs. The bonfire’s heated air caused the high branches to sway. Then suddenly the swaying branches dropped their dew load on her bonfire.

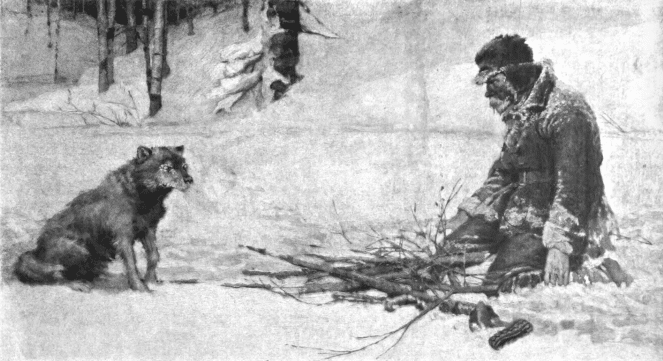

It went dead out. No fusees. No flaming boughs. No way her numb hands would let her use her emergency matches or cigarette lighter. As she looked about, her eyes noticed the wildfire sitting across the ruins of the fire from her. It was making uneasy movements, slightly lifting one flame and then another. The sight of the wildfire put a wild idea into her head. She remembered stories Ol’ Buddy told of the times, when safety officers weren’t looking, they would charge into the fire and drag out flaming debris to burn-out a good blackline to fortify their skimpy hand line.

She spoke to the wildfire, coaxing it to ignite more fuel. But in her voice was a strange note of fear that frightened the wildfire. It had never known the woman to speak in such a tone before. Something was wrong and it sensed danger. It knew not what danger, but somewhere in its core a fear arose of the woman. It flattened its flames at the sound of the woman’s voice; its uneasy sparking and the liftings and sinking of its flames became more noticeable. But it would not burn more fuel for the woman. She got down on her hands and knees and went toward the wildfire. But this unusual position again excited fear and the wildfire withered and waned. The woman sat in the ashes for a moment and struggled for calmness. Then she pulled on her gloves, using her teeth, and then stood on her feet. She glanced down to assure herself that she was really standing, because lack of feeling in her feet gave her no relation to the earth.

Her position, however, removed some fear from the wildfire. When she commanded the wildfire with her usual confident voice, the wildfire obeyed and produced some flaming debris. As the flames rose within her reach, the woman lost control. Her arms stretched out to hold a burning branch and she experienced real surprise when she discovered that her hands could not grasp. There was neither bend nor feeling in the fingers. She had forgotten for the moment that they were swollen and numb and that they were swelling more and more. All this happened quickly and before the flaming branch could escape, she encircled it with her forearms. She dragged it some 15 paces and then sat down in the ash. And in this fashion held the flaming branch, while it sparked and sputtered. But it was all she could do: hold the branch encircled in her forearms and sit there. She realized that she could not drag the torch away to burn-out the flashy fuel. There was no way to do it. With her swollen hands she could neither drag nor hold the flaming debris. Nor could she drag it away to where she wanted before it lost its heat. She dropped it and it died immediately, still sparking. The wildfire, about 40 feet away, observed her curiously, with flames meekly bent forward.

She laid back in the cold ash, defeated and dejected. As the pain and numbness seemed to cast a euphoric spell across her body, she imagined herself back at her spike camp with the boys. She would say to Ol’ Buddy, “You know that flaming spruce bough trick you told me about? As good as a drip torch, you claimed? It didn’t work. Have you ever actually tried it? I think you’re full of it!” The boys would laugh and hoot and elbow Ol’ Buddy. Then they would give her tributes of hearty back slaps. She breathed strongly and calmly and began to accept her defeat. She drifted off into a dream of her spike camp and the boys, with camaraderie and laughter and the warm glow of a campfire, swaddling her in belonging. Then her radio crackled.

The boys wanted her to answer. They wanted her back at their spike camp. She sat up and found some of her numbness had subsided. Using her teeth and club-like hands, she managed to throw together her firepack and then shrugged it on. She cradled her pulaski in her forearms and began her limping stagger back to their spike camp. Back to those lazy boys who had abandoned her. Back to those boys who honored her in victory and defeat. She turned her back on her unbuilt backfire.

Never in the wildfire’s experience had it known a woman to lay like that in the ash and make no firefight. As the inversion began to lift, the wildfire’s eager longing for the fuel mastered it. With much flaring and smoking, it sparked softly. Then it flattened its flames, expecting the woman’s curse. But the woman remained silent and hobbled away. Later, the wildfire roared loudly. And still later it moved close to where the woman had laid down and caught the smell of dead fusees. This made the wildfire back away. A little longer it delayed, crackling under the sunbeams that broke through the inversion while flames leapt and danced and shone brightly in the bluing sky. When the inversion finally fully dissipated, the wildfire turned and burned along the trail toward the camp it knew, where there were the other fuel providers who would join the firefight.