History never repeats itself but it rhymes: Rim Fire redux

The year was 1961. President Robert F. Kennedy was President of the United States. The Central Valley Project had been built and the growing San Joaquin Valley agribusiness gave way to traditional ranchland in the oak savanna of the Sierra foothills southwest of Yosemite National Park. The Harlow Fire started on July 10th. The following day it exploded, burning over 20,000 acres in two hours, vaporizing the communities of Ahwahnee and Nipinnawasee, and killing an elderly couple. Supposedly, that run on the Harlow Fire was one of the fastest ever recorded. The communities would never recover. It chased ranchers in their ranch trucks and would eventually burn into Oakhurst, scorching over 43,000 acres. This event is etched into the cultural memory of the people that live here and into the institutional memory of the organization tasked with protecting this “state responsibility area” or SRA, Cal Fire, or as it was known back in the day, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection.

Fast forward to 2018, the present, less than two weeks ago. On Friday, the 13th ,of July, deep in the Merced River Canyon at the confluence with the South Fork of the Merced…another fire started. It’s cause is still under investigation, but the following morning Cal Fire dozer operator Braden Varney was trying to push in a control line around the scattered dwellings in the canyon, when his dozer rolled and he was killed. Worse yet, his body could not be extracted before the fast-moving fire burned over the site. His body was recovered a few days later. For an occupation often dramatized as an epic struggle between man and nature, nature had drawn first blood and taken a comrade. Cal Fire now had more than just passing interest in this fire, and there was the Harlow Fire…

Braden was a second generation firefighter and a graduate of Mariposa High School, a proud source of wildland firefighters for all the nearby agencies – Cal Fire, National Park Service, U.S. Forest Service. Since this new fire, the Ferguson Fire, had escaped initial attack and was burning largely on the Sierra National Forest, a Federal Type 2 Incident Management Team (IMT) was assigned. Mariposa Pines and Jerseydale were evacuated, as well as residents in the Merced River Canyon. One of three vital access points for Yosemite visitors coming from the west was closed, including the one most used by employees.

By the evening of the July 15th the Ferguson Fire was 9,246 acres in size, and by the 16th there was enough of a threat to communities outside of the Sierra National Forest that the IMT managing the fire went into unified command with Cal Fire and the Mariposa County Sheriff’s Office. The Incident Command Post and associated fire camp quickly outgrew the Mariposa County Fairgrounds, and was moved to the Ahwahnee County Park – ground zero from 57 years ago. By the end of the 18th, as the fire continued to burn away in needle-draped brush, grass and timber, much of it dead from a devastating region-wide bug- and drought-kill event, the fire reached over 20,000 acres. The Type 2 IMT had been outmatched, and a Federal Type 1 IMT took over the fire at 6:00 am on Thursday, July 19th. Comparisons to the Harlow Fire abound. The next day, the fire crossed the Merced River to the north, despite the IMT having known about the squirrely winds expected in this sharply-angled part of the Merced Canyon where Ned’s Gulch empties into the Merced forming the well-known rapid of the same name.

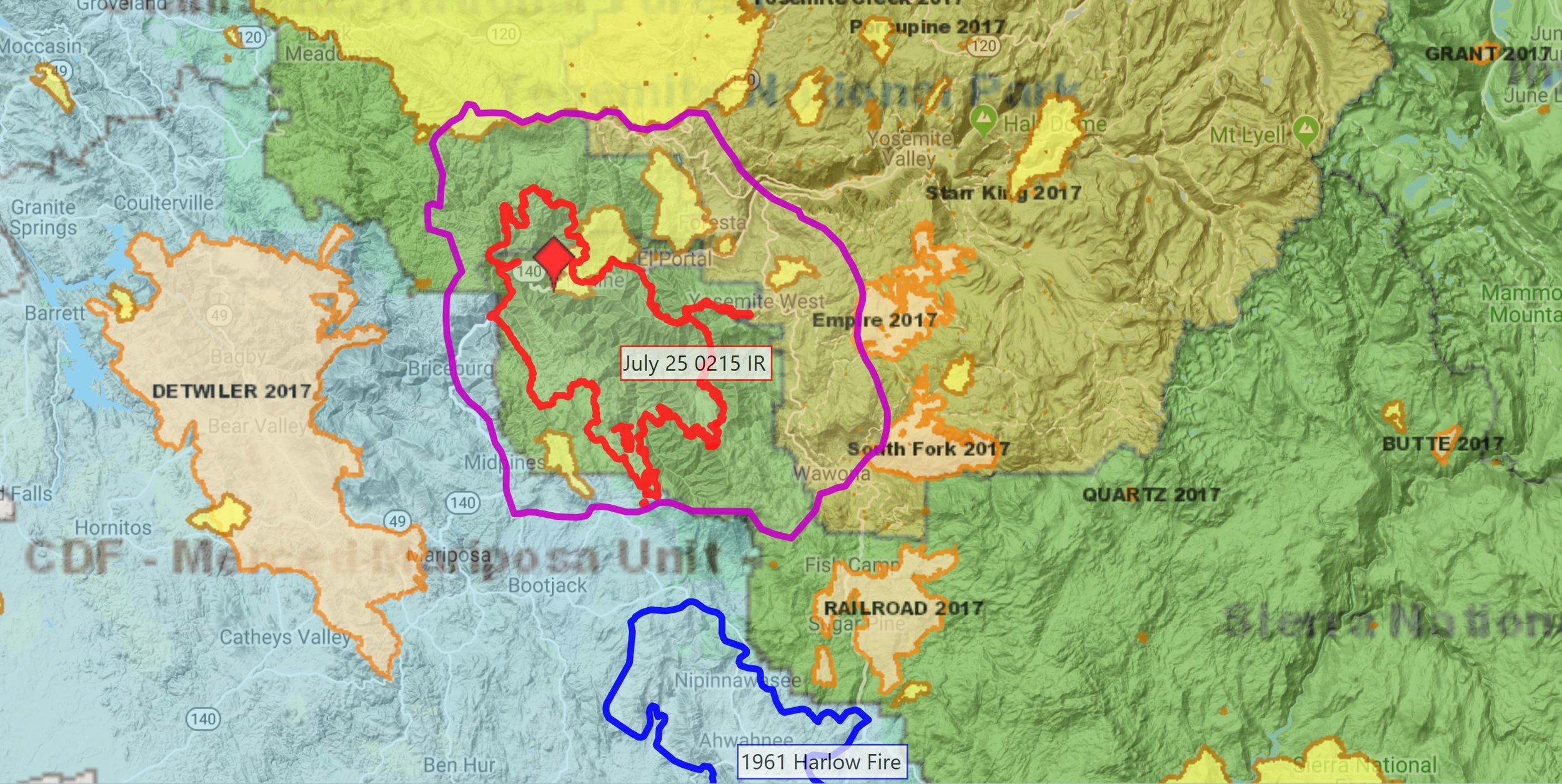

Ferguson Fire Perimeter showing the 1961 Harlow Fire (blue), fires from 2010 to 2016 (yellow, including the 2013 Rim Fire to the north), and last year’s fires (orange).

The people around Oakhust and Mariposa were in no mood for another season of revenue lost to smokey skies. In the past recent years these communities, more than most, have suffered the effects of nearby wildland fires. Just last year the Detwiler and Railroad Fires had scorched over 94,000 acres combined, the latter nearly entering Yosemite from the south. The area was smoked out for months, and business owners were bitter towards the lost revenue. No longer the hardscrabble ranches and sparse buildings of a rural area, the key locations for access into Yosemite, the so-called “gateway communities,” were now choked with the urban and suburban development with tens of thousands of homes and vast hotel complexes occupying huge tracts right up to the edge of U.S. Forest Service lands, that form a buffer between the unchecked development and the crown jewel, Yosemite. If the Ferguson Fire were to broach the divide between the South Fork Merced and the Chowchilla River drainage, it could be the Harlow Fire all over again. Descending from timber into the brush and grass, a fire of the same speed and magnitude, with the same direction of spread would be deadly and destructive at a level almost unimaginable. Cal Fire has every reason to be deeply concerned.

Yet, in Yosemite National Park, managers were weighing their options should the Ferguson Fire enter Yosemite. They had been busy in 2017 as well, managing large lightning-started fires in Yosemite’s high country. The South Fork and Empire Fires totaled some 15,650 acres and were about the same size, high in the park’s red fir and subalpine region. Doubtless they faced much adversity from residents over smoke impacts, already weary of the larger fires in their midst. These fires now serve as the catcher’s mitt, with which managers hope to catch the Ferguson Fire.

Yosemite National Park is no stranger to prescribed burning and managing lightning fires in their high country. Starting in the mid- to late-1960’s, Dr. Harry Biswell, the controversial UC Berkeley professor and his graduate student, the now-retired Yosemite Fire Ecologist Dr. Jan Van Wagtendonk, lit fires under the ancient Ponderosa pine along Studhorse Ridge above the Wawona Hotel. Since then, this park has applied fire to the landscape time and time again. In some places around Wawona fires have been lit 5-6 times in the five decades since, leaving a beautiful old fire-resistant ponderosa pine overstory and lush carpet of bear clover between the widely-spaced large diameter trees. The thick accumulation of brush, larger woody debris and carpet of young shade-tolerant white fir, often acting as a ladder fuel, were much reduced. Sadly, some of these mature trees succumbed to the drought and insects, but they still remain as habitat to the many creatures that inhabit big, old dead trees - those standing and those fallen to the forest floor.

Managers in Yosemite National Park and Sequoia-Kings National Park had re-learned or embraced what Native Americans have known for millennia – in dry forests where cast-off woody material accumulates and doesn’t decompose quickley, fires need to be encouraged under controlled conditions, depriving the subsequent unplanned-for blaze of fuel that could reach to the crowns, triggering larger swaths of overstory mortality. They also learned of the need for fire to create a fuelbed to nurture Giant Sequoia seedlings. Indeed, the lack of fire is more threatening to a mature grove of Sequoias than is a fire. Last year the U.S. Forest Service’s Nelder Grove of Giant Sequoias was damaged in the Railroad Fire. Damage, which could have been reduced by proactive understory small-diameter thinning and prescribed burning.

On July 21st the Ferguson Fire had crossed the Merced River and was in alignment with the wind burning in 30-year old decadent chamise brush left behind by the 1987 Larson Fire. It was moving north quickly, and looked as though it might reach the 2013 Rim Fire.

Fire retardant holds the west flank of the slopover across the Merced River onto the Stanislaus N.F.

Fires were filling in all the gaps in bug-killed and drought-stressed vegetation accumulated over a decade on a grand scale in the foothills of Mariposa and Madera Counties, similar to the heralded Illillouette drainage high above Yosemite Valley, where fire ecologists noted the same pattern of self-organizing burn scars on the landscape, after National Park staff allowed lightning fires to burn there.

By now there were two tall columns visible, one from the north end of the Ferguson Fire making its way north toward the Rim Fire, and one from the south end where a pocket of dense timber was burning in Granite Creek and in the bug-killed trees and brush above Jerseydale, where firefighters were struggling to keep the fire within primary control lines. Snags were reportedly falling within thirty short minutes of catching fire on a dangerous night shift spent dodging falling debris, while burning out along this critical line.

Ferguson Fire column from ICP on July 22nd

By the July 23rd smoke was choking Yosemite Valley, the Merced River Canyon and beyond. Hazardous levels of smoke exceeding a bad day in Bejing were being consistently recorded in the Valley, and the right, ethical decision was made to close the busiest part of the park - Yosemite Valley. Should workers be forced to endure unhealthy conditions to keep the park operating? Should the underpaid kids working for park concessions from impoverished places like Eastern Europe be shackled to their grills and dish sinks to accommodate the global wealthy travelers? Business owners reaping vast profit from businesses near Yosemite would do well to remember where their bread is buttered – the towering granite massifs and some old trees protected by the park’s fire program, which will remain after the fires quiet. How ironic that the business owners and a smaller percentage of the public who had complained in past years about because of the “nuisance” of smoke from Yosemite's prescribed burning and high country wildfires were now eating smoke big-time from a wildfire burning outside the park, where much less prescribed burning had occurred.

A public meeting was held in Yosemite Valley at 11:00am on the 24th and by that night firefighters were using the park's past prescribed burning sites to assist in their lighting fire on Henness Ridge to aid in the protection of the ridgetop community of Yosemite West on the park’s west flank. Parts of Yosemite were closed the next day on Wednesday, the 25th. According to USA Today, it was the first time Yosemite Valley was closed for a wildfire in nearly 30 years, a testament to the parks fire program, in that despite all the fire being managed to reduced fuels during that time, park facilities in Yosemite Valley were able to stay open. The Ferguson Fire now seems poised to be what the Rim Fire was to the north side of the park. Yosemite’s past practice of prescribed burning and managing natural fires saved thousands of acres of old-growth Ponderosa pine, incense cedar and sugar pine, including the Tuolumne Grove of Giant Sequoia, as well as modified the behavior and severity of thousands of acres more during the 2013 Rim Fire. Those past practices will prove vital in the days and weeks to come around Yosemite West, Wawona, and possibly even the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias.

Looking up Ned’s Gulch where the Ferguson Fire jumped the Merced River, destroying old mining era structures there.

At this moment, the Ferguson Fire is a tale of two fires. One is the Wildland Urban Interface or WUI fire. That’s the fire on the southwest and south flank that threatens to come roaring down the Chowchilla River drainage into a human-built nightmare of winding, narrow roads and thousands of homes and businesses. Here, let Cal Fire honor their fallen by protecting the people at risk in the foothills with whatever means necessary – aircraft, dozers, drones, and every other piece of “big iron” as it is called, being deployed with all the associated resource damage that may cause. The other fire – the real wildland fire – moving steadily southward into the Chowchilla Mountains above Wawona is burning toward the birthplace of Yosemite’s prescribed fire laboratory.

Generations of fire managers in Yosemite have chipped away at the fuels reaching a high point in the eighties through the first decade of the 21st Century, diminishing with the shrinking budgets after the Great Recession and growing concerns over the air quality in the San Joaquin Valley. There they toiled away, facing the slings and arrows of both the public and management when smoke events choked Yosemite Valley, or in the one notable case when a prescribed fire that had an unintended outcome, against a backdrop of hundreds of successful instances when fire was used as a tool.

Even the Madera Review as late as July 1967, while remembering the Harlow Fire six years before, espoused the conventional wisdom passed down from Native Americans to the Anglo and Hispanic ranching communities,

"Frequent supervised control burns are major factors in reducing stands of brush and dead trees which provide fuel for onrushing flames."

Firefighters finish burning out around a house in the Merced River canyon.

In early 2017, before the State's most deadly 2018 season, Cal Fire’s Chief, Ken Pimlott, called for a tripling of acres burned by the agency that has prided itself and built a culture of being a pure suppression organization. Cal Fire, across the span of its existence, has often criticized other agencies, Native American Tribes and private landowners in their attempts to use fire constructively, preferring the more simply-explained “put the wet stuff on the red stuff.” In May of 2017 a recent sign-on letter of environmental groups challenged CalFire for acknowledging the climate-driven risk of wildfire by purchasing more equipment, but not adequately funding prescribed fire and other fuel treatments around communities.

Whether you believe in human-induced climate change or not, and no matter the cause of the widespread tree mortality, nor the varied agency cultures, firefighters of all stripes - federal, state, county and local government all have to play nice in California’s sandbox as climate chaos frays nerves and takes lives, much as it has most recently in the California-like Mediterranean environments of Greece and Portugal. All the agencies must pool their resources and come together under the Incident Command System, or ICS, in order to protect the people and structures in Ahwahnee and Nipinnawasee from the WUI fire threat posed by the Ferguson Fire.

In Yosemite, managers are ready to receive the Ferguson wildland fire, should it cross the South Fork below the Wawona Road, coming out of the Sierra National Forest's Devils Gulch-Ferguson Ridge roadless area and into Yosemite. Hyperbolic headlines that serve only to trigger emotionally, linking Yosemite and destruction by fire, are not helpful. Reality is much more complex. There could have always been more funding for fuel treatments, or less risk aversion by park managers over the years, but the event that was always understood to be a matter of “when” and not “if”, is upon them. Prescribed fire and thinning around Yosemite West and Wawona, connected by the “miles of piles” thinning along the Wawona Road will slow the Ferguson Fire, allowing firefighters to protect the structures there, but even these decades of burning and thinning by chainsaws will not likely stop the Ferguson Fire. The Ferguson Fire will stop high above the Wawona Raod when it runs into last year’s South Fork and Empire Fires and when the rain and snow falls again on the slopes above Badger Pass, as intended, as a dynamic natural process that will begin the process of healing from the area’s dead tree epidemic. Yosemite park managers should be praised for their foresight and preparation.